Friday, October 30, 2009

I've decided to return to my previous system of short reviews of several books, rather than lengthy reviews of books one-by-one.

Non-fiction

Fareed Zakaria - The Post-American World - [Audiobook]

I can't say much about this book, except, 'Wow, you really didn't expect the financial crisis, did you?' That said, Zakaria makes interesting and enlightening points about the US's relationships with China and India, and the potential changes in international relations that are likely to occur as a consequence of these new powers flexing their political muscles during the 21st century. But, Zakaria's economics was much more conservative than I expected them to be, advocating Chicago-style policies, without much discussion of more social support, the nuances of alleviating poverty and inequality, or the ways in which interactions between more powerful developed countries and less powerful developing countries could affect the development paths of the 'rest' - his perceptions of socialism, communism and even social democracy seemed a bit jaded and biased. Though the evidence indicates that many countries that did not grow for most of the 20th century are growing and will continue to grow in the 21st century, but this does not mean that their growth will be slower, or that it will favour specific echelons in their societies, or that new problems, particularly with inequalities in power, wealth and rights won't plague these countries, particularly China and Russia. Nevertheless, I still learnt a fair amount from this book, though not enough to warrant the overall defence of capitalism Zakaria advocates, his approach required more nuance.

Joseph J. Ellis - Founding Brothers - [Audiobook]

Joseph J. Ellis - Founding Brothers - [Audiobook]

Ellis takes a strongly episodic approach to the American revolution in Founding Brothers. He begins the book with an episode after the revolution - the duel between Alexander Hamilton and Aaron Burr. Burr shot Hamilton, after which Hamilton died. The episode illustrates a larger conflict between the Federalists and the Republicans, and how their beliefs about the intentions of the revolutionary generation affected their beliefs about the direction of the fledgling American union. We see this time and again throughout the book, manifested particularly in the animosity between Jefferson and Hamilton, in both parties' attacks on John Adams, on the name-calling (both Washington and Adams were accused of being 'monarchists'), and on myriad other events during the years immediately subsequent to the revolution.

For me, the most interesting of the larger episodes Ellis recounts is that of the evolution of the friendship between John Adams and Thomas Jefferson. Initially close as a consequence of their time spent together in the Continental Congress during which time Adams supervised Jefferson, closer still after their time together in Europe, then diverging after their return to America: Adams staunchly support of Washington (and therefore tacitly supported Hamilton) and was sceptical of the French revolution believing that it would come to no good, whereas Jefferson believed that the American Revolution were one and the same, that Washington had concentrated too much power in the presidency and that Hamilton, through Washington, was in the process of making the Union a slave of banking interests, and thus vicariously a tool of the British Empire. However, after much impugning of character, after both their presidencies, and after tragedy had befallen them both, after Jefferson came as close as he would to apologising for his conduct, they became friends once more, dying within hours of each other on the 50th anniversary of signing of the Declaration of Independence on July 4th, 1826, during the presidency of John Adams's son, John Quincy Adams.

But I found a few problems with the book. First, for someone unfamiliar with the American revolution a lot of the content and context would be missed - you need to know at least the background, surrounding structure, and consequences of the revolution to understand the episodes that Ellis recounts, though I understand this because of my own reading, others unfamiliar with the information might not. Second, as in Ellis's other book on the American revolution, American Creation, Ellis tends to try to create a myth around the evidence, rather than letting the evidence do as much speaking for itself as it can. Not that I expect a history book to be without argument or without discussion, but I prefer a history in which I hear less of the author's voice and more of the voices of those involved - letters, essays, speeches from their pens and mouths. Ellis writes quite forgivingly about his founding brothers, taking their good qualities with their bad, and relating how he believes much might not have been achieved without the synthesis, the sum greater than the parts, that they created in the American union. However, his picture still lacks some of the nuance of social history - to what extent was Washington actually indispensable? Did the history really revolve around him? What about all the Americans working and supporting the many politicians who made their names? What was their relevanceo to the founding? To the American constitution's development? To the development of democracy? So expect a detailed picture of the main players, indeed the founding brothers, and their families and acquiantances, expect biographical details without greater details of the times, locations and social context. For those look elsewhere.

David McCullough - John Adams - [Audiobook]

David McCullough - John Adams - [Audiobook]

I loved this audiobook and I came to appreciate the personality and character of John Adams while listening to it. For those of you who don't know, John Adams was the second president of the United States, succeeding George Washington, and preceding Thomas Jefferson. As the man succeeding Washington he had to deal with the relative mess left by Washington and the machinations of Hamilton, and the blooming anti-Federalist sentiments spurred by Jefferson, Madison, and the Republicans. McCullough captures well the challenges that Adams faced, articulating how his flaws impeded him and how his virtues enabled him to achieve the highest office in the land.

McCullough introduces us to Adams during the lead-up to the revolution, and then backtracks to when Adams was the oldest child of John Adams Sr., a boot maker and town alderman. John Adams Jr. studied well and went on to attend Harvard College under the supervision of such luminaries as John Winthrop and others, after which he went on to study the law. His decision to study law, rather than to become a teacher as he had intended dramatically altered his path as it gained him access to thinkers and practitioners who were on both sides of the revolutionary perspective: Tories and those in favour of opposing the British. Adams's simultaneous high quality education, his dedication to ethical and godly behaviour, his determination to be purely and incorruptibly independent in thought and deed (causing many problems later when the States became dominated by parties), his dedicated marriage to Abigail and its proto-feminist equality of intellect (she was basically his sole advisor during his presidency when he realised that his cabinet ministers were Hamilton's toadies), make Adams a phenomenally interesting man to read about. Moreover, because of the close relationship between John and Abigail, the book is as much her biography as his, except that she would not have been allowed to be the second president of the United States.

The book is supported substantially by the primary sources that the Adams family left to historians, based predominantly on the exhaustive of letters between John and Abigal, the vast collection of letters between Adams and Jefferson, Adams and so many others - Benjamin Rush, Elbridge Gerry, John Jay, The Warrens, his son John Quincy Adams (6th President of the US), several Dutch friends, to name a few. McCullough draws heavily on letters written by others too, particularly Abigail and Thomas Jefferson. In addition, McCullough recreates the context of the revolutionary colonies and then the republican United States. He provides every day details ranging from Abigail's continuous demand that John buy needles and cloth when in Philadelphia, to the worries about money, land and children.

Although John's relationship with Abigail forms the backbone of the book, his relationship with his children paints on odd picture of a the role of the rotestant father tied to duty. John believed that his life was not his own and that doing duty to God and to country were far more important than his family. His attitude led to conflict with Abigail, but also to later conflict and remonstrances from his children, particularly Thomas who never seemed to forgive his father for being distant, for being against nepotism and for arguing against any form of speculative investment (Thomas lost several thousand dollars to speculation, thousand dollars of which belonged to his brother John Quincy). Thomas died an alcoholic, leaving his wife and children to the care of his extended family. Sadly, Charles too, after insufficient success as a lawyer turned to the bottle. Nabby, the Adams's eldest child married Colonel Smith, John Adams's one-time secretary. But Col. Smith too favoured speculation and lost substantial amounts of money, losing John Adams's favour in the process. John Adams, informed greatly by his religious background I would suspect, believed that people should have pride in their work, should work determinedly, and should always avoid mummery with money and speculation particularly - simply using money to make money, rather than doing something constructive with your time and abilities was immoral in John Adams's mind. Consequently, apart from his sometimes warm, sometimes cool relationship with his son John Quincy, John Adams ended up having fairly poor relationships with his children. It seems as though this tragedy hurt him, but that he wished his children to understand that a person's life was not their own, but rather given to duty and to God. Adams's work ethic was heroic, he religiously rose at 5am, worked many hours every day, reading late into the night by candlelight. Anything less, he seemed to feel, would not be upholding his duties.

I could go on about the many lists of events, triumphs, tragedies, failures, and renewals in John Adams's life. In fact, with a biography like this, where I really felt compassion and appreciation for the person being written about, it is difficult to determine whether the biography itself is worthwhile. However, I believe that David McCullough's presentation of the narrative does lend one to appreciate John Adams, but it also enables us to see Adams's flaws and his understanding of these flaws. McCullough therefore writes good popular biographical history - allowing us access to the inner life of the main character of the history, while illuminating us about their many quirks and foibles. I recommend this book because it allowed me access to the history of a man who so evidently felt passionately and worked devotedly on behalf of his country and its union.

Thomas Paine - Common Sense - [Audiobook]

Thomas Paine - Common Sense - [Audiobook]

I read Common Sense because it is referred to in all the books I've read recently on the American Revolution. Almost all of these books argue that revolutionary sentiments were not sufficiently high to justifyrevolution prior to Paine writing and publishing Common Sense, but after he published it sentiments tended far more towards independence than they had before. The change enabled the continental congress to vote on independence, rather than favouring re-integration with Great Britain alongside greater colonial power in parliament. Paine's work should also be seen as part of a larger project within The Enlightenment in which philosophers and commentators grappled with the problems of liberty, representation, science and the role of the state. I strongly recommend reading this as a way to access the

prevailing sentiments in the colonies that were to become the United States.

Fiction

Alice Sebold - The Lovely Bones -

Alice Sebold - The Lovely Bones -

In The Lovely Bones, Sebold tells the story of an adolescent girl, Susie Salmon who is raped and murdered, and then ascends to heaven. The story is told from Susie's perspective, as she observes people on earth, and the novel spans several years after Susie's death.

Susie details her parents' relationship after her death - her father's obsession with finding her murderer, and her mother trying simply to 'get on with life'. Susie shows too the development of her sister, Lindsey, from an awkwardly gifted, yet beautiful younger sister to someone reconciled with her sisters death. She charts the growth of her brother, Buckley, from someone confused by the sudden disappearance of a sister who had always been there, to someone who knows and understands. She describes the path taken by the boy she liked in school, Ray Singh, as he moves on from being the intelligent and considerate outsider. Susie portrays too the life of her friend, Ruth, a school misfit convinced that ghosts exist, that she is watched, and uncertain whether she is attracted to men or women.

Though one of the main ideas behind the novel, that Susie's murderer continues to live down the road from her parents, could detract from the novel, it doesn't because the novel is not, ultimately, a detective novel or a whodunnit of any sort. Rather, you should take this novel as an interesting confessional or detail-oriented and compassionate portrait of family life after death.

There are several intriguing facets to The Lovely Bones seen mainly in Susie's contemplations and actions: from trying to cross over from heaven to earth and touching those who live on earth in an urge to manipulate what occurs on earth, to lamenting what she has missed because she was killed while remonstrating herself for those things she did not do while alive, to accepting where she is and releasing her attachment to those on earth. Sebold achieves a fairly innovative novel, which I found enjoyable to read. It won't change your world, but you'll gain a sense of a family's suffering after death and how that family strives for resolution, written in a way that feels compassionate and new. Don't be deceived into thinking it's the novel of the century as some reviews would have you believe, but rather that it's fairly slow-moving, thorough and enjoyable if you don't have crazy expectations.

Stella Gibbons - Cold Comfort Farm -

Stella Gibbons - Cold Comfort Farm -

Written in 1932, Cold Comfort Farm is a satirical take on the Victorian novel and the heroins that populated the work of Jane Austen, the Brontes, Elizabeth Gaskell, and others. Gibbons plays up the polarity of rural vs. urban, illuminates the machinations required to make a love overcome class barriers, while making a laugh of it all. Reading Cold Comfort Farm, you get a sense of the doomy and gloomy become spirited and bright, with a manipulative nudge, spit and polish, hard work, and determination. Flora Post, the protagonist, takes on the curse of the farm, the will of her dreadfully backward, suspicious and superstitious family and turns their lives on their head, changing the lives of the surrounding quasi-nobility and villagers in the process. The book must be read to be believed, and you'll laugh your way through it, especially if you know and understand 19th century English fiction. Have a read, it's easy and enjoyable.

Paul Auster - The New York Trilogy

Paul Auster - The New York Trilogy

I find it difficult to comment on Auster's trilogy, mainly because the books, though creating a unified whole, also seem to jar, to rub against each other oddly. That said, they constitute a masterpiece of post-modern literature, consistently playing with the notion of authorship, the position of the author in the novel, the nature of autobiogrpahy and biography, and embedding post-modern theorizing and playfulness in a well-known genre: the detective novel.

I thoroughly enjoyed the first and third parts of the trilogy, becoming slightly annoyed by the second part while I read it, but then understanding its relevance to the whole once I reached the end of the novel. It would not have worked without the annoying, but still well-written, second section. My annoyance derived from the post-modern ploys that Auster adopted to achieve his end result, the relevance of which I understand, but I remained annoyed by them. But don't let this detract from the novel too much, the first and third sections are sublime. The third section takes the first two, builds on the structure they provide, and makes the entire novel into something enchanting and truly worthwhile. If you struggle a bit in the middle of the book, champion onward - you will be rewarded by a well-plotted literary detective novel that achieves several 'Ahah!' moments. Enjoy them.

Tracy Chevalier - Burning Bright

Tracy Chevalier - Burning Bright

1/2

1/2

I expected more of Burning Bright, having been told that Chevalier wrote Girl With a Pearl Earring, which I've yet to read, but I have been told is good. I was not to be satisfied. In the book, Chevalier tries to depict London during the Romantic era, playing too with the ideas beloved by the Romantics, for example the beauty of the rural and the corruption of the urban. But her execution of these ideas is clumsy, and they almost lose relevance as a consequence, which the Romantics themselves would have lamented - Coleridge twists in his grave.

The plot progresses as follows. A family from the good rural areas up North, move down to London when opportunity calls. But they are led astray by the allures of the city - they end up poorer than they began, tales of woe hound them, one of the few thins to make their lives seem worthwhile is the assistance they are given by one Mr. William Blake, their neighbour in Lambeth. William Blake meets the two main characters of the book - a boy and a girl - for whom he tries to explain the nature of innocence and experience, an ongoing conversation in which Blake expounds on how everyone has some innocence and some experience in them, and that each person but finds themselves somewhere on the continuum. Rah rah! Enter caddish lad, all suave atop a military horse, who navigates a lady's innocence and makes her more experienced. Ho hum. The book had a lot of potential, there was so much that could be done with the character of William Blake and the people who surrounded him, but it was not to be.

Instead, somehow, Chevalier manages to take the good bits, peel many of them away, and trivialize what remains by turning it into something puerile and arbitrary. If you've read Songs of Innocence and Experience, then you'd know that Blake plays with the these notions deliberately, plays with ideas of religion, of youth, of age, of creation and destruction. Yes, these come through in Chevalier's story, but so obviously and clumsily that they are far less appreciable than in William Blake's poetry. I'd recommend that instead of reading this book, reading a biography of William Blake, read some of his poetry, and maybe read a bit about the history of London at the time.

Annie Dilard - The Maytrees

Rarely do I read a book that conjures images as vividly and imaginatively as those that Annie Dillard conjures in The Maytrees. A love story, the book charts the love of a couple living in Provincetown on the Eastern Coast of the United States: they give birth to a child, they rift, but where does love go? What happens to love? Does it vanish? remain? transform? Can you love more than one person at a time? What of children?

I consistently read passages of The Maytrees out to my wife, astounded by Dillard's ability to characterize moments and sensations perfectly, for example, "They shook hands and hers felt hot under sand like a sugar donut," (7) or "Lou saw the sun spread like a gull for its landing on the sea." (105) Both are beautiful comparisons and evoke the exact image, the exact sensation to make me, as a reader, feel and see what the author makes the characters feel and see in these moments.

The Maytrees is stately, it carried me on the ebbs and flows of its prose as it would a piece of driftwood, and I had to give in to the rhythms of it, let it speak to me slowly, occasionally overwhelmed, occasionally feeling as though I sat atop a wave and was glimpsing an horizon beyond the book. Ok, I'm over-writing now, but I simply wanted to say I thought the book beautiful, poignant, poetic. It will not suit everyone, not that much 'happens'. Much is shown for us to interpret and relay, but I believe that if you appreciate Dillard's writing style, I have but read The Writing Life, The Maytrees will reward you with equally good steadily unfurling beauty and truth about love.

Raymond E. Feist - The Serpentwar Saga and The Conclave of Shadows Trilogy

I've read these books a number of times. Having recently been moving country, staying in a friend's living room, finding an apartment,

moving, getting internet, signing contracts, getting work, etc, I needed something non-literary. I fly through these books when I read

them and they satisfy a strange urge for reading about heroes, battles, magic, etc. Feist does epic battles, multiple-world-spanning wars, and bad philosophy about gods and people well. The Serpentwar Saga probably contains one of my favourite books of his Rise of a Merchant Prince, in which the main character, Rupert Avery, tries to set up a trading empire. Feist details how Roo fails, has the chutzpah to try something phenomenal, triumphs, then loses a huge amount of money in the next book because of a war, after which he starts up again in an attempt to regain his wealth amidst the ashes of a burnt-out kingdom. Thrilling stuff. Just what I needed while dealing with admin and getting back into a working paper on risk aversion.

Non-fiction

Fareed Zakaria - The Post-American World - [Audiobook]

I can't say much about this book, except, 'Wow, you really didn't expect the financial crisis, did you?' That said, Zakaria makes interesting and enlightening points about the US's relationships with China and India, and the potential changes in international relations that are likely to occur as a consequence of these new powers flexing their political muscles during the 21st century. But, Zakaria's economics was much more conservative than I expected them to be, advocating Chicago-style policies, without much discussion of more social support, the nuances of alleviating poverty and inequality, or the ways in which interactions between more powerful developed countries and less powerful developing countries could affect the development paths of the 'rest' - his perceptions of socialism, communism and even social democracy seemed a bit jaded and biased. Though the evidence indicates that many countries that did not grow for most of the 20th century are growing and will continue to grow in the 21st century, but this does not mean that their growth will be slower, or that it will favour specific echelons in their societies, or that new problems, particularly with inequalities in power, wealth and rights won't plague these countries, particularly China and Russia. Nevertheless, I still learnt a fair amount from this book, though not enough to warrant the overall defence of capitalism Zakaria advocates, his approach required more nuance.

Joseph J. Ellis - Founding Brothers - [Audiobook]

Joseph J. Ellis - Founding Brothers - [Audiobook] Ellis takes a strongly episodic approach to the American revolution in Founding Brothers. He begins the book with an episode after the revolution - the duel between Alexander Hamilton and Aaron Burr. Burr shot Hamilton, after which Hamilton died. The episode illustrates a larger conflict between the Federalists and the Republicans, and how their beliefs about the intentions of the revolutionary generation affected their beliefs about the direction of the fledgling American union. We see this time and again throughout the book, manifested particularly in the animosity between Jefferson and Hamilton, in both parties' attacks on John Adams, on the name-calling (both Washington and Adams were accused of being 'monarchists'), and on myriad other events during the years immediately subsequent to the revolution.

For me, the most interesting of the larger episodes Ellis recounts is that of the evolution of the friendship between John Adams and Thomas Jefferson. Initially close as a consequence of their time spent together in the Continental Congress during which time Adams supervised Jefferson, closer still after their time together in Europe, then diverging after their return to America: Adams staunchly support of Washington (and therefore tacitly supported Hamilton) and was sceptical of the French revolution believing that it would come to no good, whereas Jefferson believed that the American Revolution were one and the same, that Washington had concentrated too much power in the presidency and that Hamilton, through Washington, was in the process of making the Union a slave of banking interests, and thus vicariously a tool of the British Empire. However, after much impugning of character, after both their presidencies, and after tragedy had befallen them both, after Jefferson came as close as he would to apologising for his conduct, they became friends once more, dying within hours of each other on the 50th anniversary of signing of the Declaration of Independence on July 4th, 1826, during the presidency of John Adams's son, John Quincy Adams.

But I found a few problems with the book. First, for someone unfamiliar with the American revolution a lot of the content and context would be missed - you need to know at least the background, surrounding structure, and consequences of the revolution to understand the episodes that Ellis recounts, though I understand this because of my own reading, others unfamiliar with the information might not. Second, as in Ellis's other book on the American revolution, American Creation, Ellis tends to try to create a myth around the evidence, rather than letting the evidence do as much speaking for itself as it can. Not that I expect a history book to be without argument or without discussion, but I prefer a history in which I hear less of the author's voice and more of the voices of those involved - letters, essays, speeches from their pens and mouths. Ellis writes quite forgivingly about his founding brothers, taking their good qualities with their bad, and relating how he believes much might not have been achieved without the synthesis, the sum greater than the parts, that they created in the American union. However, his picture still lacks some of the nuance of social history - to what extent was Washington actually indispensable? Did the history really revolve around him? What about all the Americans working and supporting the many politicians who made their names? What was their relevanceo to the founding? To the American constitution's development? To the development of democracy? So expect a detailed picture of the main players, indeed the founding brothers, and their families and acquiantances, expect biographical details without greater details of the times, locations and social context. For those look elsewhere.

David McCullough - John Adams - [Audiobook]

David McCullough - John Adams - [Audiobook] I loved this audiobook and I came to appreciate the personality and character of John Adams while listening to it. For those of you who don't know, John Adams was the second president of the United States, succeeding George Washington, and preceding Thomas Jefferson. As the man succeeding Washington he had to deal with the relative mess left by Washington and the machinations of Hamilton, and the blooming anti-Federalist sentiments spurred by Jefferson, Madison, and the Republicans. McCullough captures well the challenges that Adams faced, articulating how his flaws impeded him and how his virtues enabled him to achieve the highest office in the land.

McCullough introduces us to Adams during the lead-up to the revolution, and then backtracks to when Adams was the oldest child of John Adams Sr., a boot maker and town alderman. John Adams Jr. studied well and went on to attend Harvard College under the supervision of such luminaries as John Winthrop and others, after which he went on to study the law. His decision to study law, rather than to become a teacher as he had intended dramatically altered his path as it gained him access to thinkers and practitioners who were on both sides of the revolutionary perspective: Tories and those in favour of opposing the British. Adams's simultaneous high quality education, his dedication to ethical and godly behaviour, his determination to be purely and incorruptibly independent in thought and deed (causing many problems later when the States became dominated by parties), his dedicated marriage to Abigail and its proto-feminist equality of intellect (she was basically his sole advisor during his presidency when he realised that his cabinet ministers were Hamilton's toadies), make Adams a phenomenally interesting man to read about. Moreover, because of the close relationship between John and Abigail, the book is as much her biography as his, except that she would not have been allowed to be the second president of the United States.

The book is supported substantially by the primary sources that the Adams family left to historians, based predominantly on the exhaustive of letters between John and Abigal, the vast collection of letters between Adams and Jefferson, Adams and so many others - Benjamin Rush, Elbridge Gerry, John Jay, The Warrens, his son John Quincy Adams (6th President of the US), several Dutch friends, to name a few. McCullough draws heavily on letters written by others too, particularly Abigail and Thomas Jefferson. In addition, McCullough recreates the context of the revolutionary colonies and then the republican United States. He provides every day details ranging from Abigail's continuous demand that John buy needles and cloth when in Philadelphia, to the worries about money, land and children.

Although John's relationship with Abigail forms the backbone of the book, his relationship with his children paints on odd picture of a the role of the rotestant father tied to duty. John believed that his life was not his own and that doing duty to God and to country were far more important than his family. His attitude led to conflict with Abigail, but also to later conflict and remonstrances from his children, particularly Thomas who never seemed to forgive his father for being distant, for being against nepotism and for arguing against any form of speculative investment (Thomas lost several thousand dollars to speculation, thousand dollars of which belonged to his brother John Quincy). Thomas died an alcoholic, leaving his wife and children to the care of his extended family. Sadly, Charles too, after insufficient success as a lawyer turned to the bottle. Nabby, the Adams's eldest child married Colonel Smith, John Adams's one-time secretary. But Col. Smith too favoured speculation and lost substantial amounts of money, losing John Adams's favour in the process. John Adams, informed greatly by his religious background I would suspect, believed that people should have pride in their work, should work determinedly, and should always avoid mummery with money and speculation particularly - simply using money to make money, rather than doing something constructive with your time and abilities was immoral in John Adams's mind. Consequently, apart from his sometimes warm, sometimes cool relationship with his son John Quincy, John Adams ended up having fairly poor relationships with his children. It seems as though this tragedy hurt him, but that he wished his children to understand that a person's life was not their own, but rather given to duty and to God. Adams's work ethic was heroic, he religiously rose at 5am, worked many hours every day, reading late into the night by candlelight. Anything less, he seemed to feel, would not be upholding his duties.

I could go on about the many lists of events, triumphs, tragedies, failures, and renewals in John Adams's life. In fact, with a biography like this, where I really felt compassion and appreciation for the person being written about, it is difficult to determine whether the biography itself is worthwhile. However, I believe that David McCullough's presentation of the narrative does lend one to appreciate John Adams, but it also enables us to see Adams's flaws and his understanding of these flaws. McCullough therefore writes good popular biographical history - allowing us access to the inner life of the main character of the history, while illuminating us about their many quirks and foibles. I recommend this book because it allowed me access to the history of a man who so evidently felt passionately and worked devotedly on behalf of his country and its union.

Thomas Paine - Common Sense - [Audiobook]

Thomas Paine - Common Sense - [Audiobook] I read Common Sense because it is referred to in all the books I've read recently on the American Revolution. Almost all of these books argue that revolutionary sentiments were not sufficiently high to justifyrevolution prior to Paine writing and publishing Common Sense, but after he published it sentiments tended far more towards independence than they had before. The change enabled the continental congress to vote on independence, rather than favouring re-integration with Great Britain alongside greater colonial power in parliament. Paine's work should also be seen as part of a larger project within The Enlightenment in which philosophers and commentators grappled with the problems of liberty, representation, science and the role of the state. I strongly recommend reading this as a way to access the

prevailing sentiments in the colonies that were to become the United States.

Fiction

Alice Sebold - The Lovely Bones -

Alice Sebold - The Lovely Bones - In The Lovely Bones, Sebold tells the story of an adolescent girl, Susie Salmon who is raped and murdered, and then ascends to heaven. The story is told from Susie's perspective, as she observes people on earth, and the novel spans several years after Susie's death.

Susie details her parents' relationship after her death - her father's obsession with finding her murderer, and her mother trying simply to 'get on with life'. Susie shows too the development of her sister, Lindsey, from an awkwardly gifted, yet beautiful younger sister to someone reconciled with her sisters death. She charts the growth of her brother, Buckley, from someone confused by the sudden disappearance of a sister who had always been there, to someone who knows and understands. She describes the path taken by the boy she liked in school, Ray Singh, as he moves on from being the intelligent and considerate outsider. Susie portrays too the life of her friend, Ruth, a school misfit convinced that ghosts exist, that she is watched, and uncertain whether she is attracted to men or women.

Though one of the main ideas behind the novel, that Susie's murderer continues to live down the road from her parents, could detract from the novel, it doesn't because the novel is not, ultimately, a detective novel or a whodunnit of any sort. Rather, you should take this novel as an interesting confessional or detail-oriented and compassionate portrait of family life after death.

There are several intriguing facets to The Lovely Bones seen mainly in Susie's contemplations and actions: from trying to cross over from heaven to earth and touching those who live on earth in an urge to manipulate what occurs on earth, to lamenting what she has missed because she was killed while remonstrating herself for those things she did not do while alive, to accepting where she is and releasing her attachment to those on earth. Sebold achieves a fairly innovative novel, which I found enjoyable to read. It won't change your world, but you'll gain a sense of a family's suffering after death and how that family strives for resolution, written in a way that feels compassionate and new. Don't be deceived into thinking it's the novel of the century as some reviews would have you believe, but rather that it's fairly slow-moving, thorough and enjoyable if you don't have crazy expectations.

Stella Gibbons - Cold Comfort Farm -

Stella Gibbons - Cold Comfort Farm - Written in 1932, Cold Comfort Farm is a satirical take on the Victorian novel and the heroins that populated the work of Jane Austen, the Brontes, Elizabeth Gaskell, and others. Gibbons plays up the polarity of rural vs. urban, illuminates the machinations required to make a love overcome class barriers, while making a laugh of it all. Reading Cold Comfort Farm, you get a sense of the doomy and gloomy become spirited and bright, with a manipulative nudge, spit and polish, hard work, and determination. Flora Post, the protagonist, takes on the curse of the farm, the will of her dreadfully backward, suspicious and superstitious family and turns their lives on their head, changing the lives of the surrounding quasi-nobility and villagers in the process. The book must be read to be believed, and you'll laugh your way through it, especially if you know and understand 19th century English fiction. Have a read, it's easy and enjoyable.

I find it difficult to comment on Auster's trilogy, mainly because the books, though creating a unified whole, also seem to jar, to rub against each other oddly. That said, they constitute a masterpiece of post-modern literature, consistently playing with the notion of authorship, the position of the author in the novel, the nature of autobiogrpahy and biography, and embedding post-modern theorizing and playfulness in a well-known genre: the detective novel.

I thoroughly enjoyed the first and third parts of the trilogy, becoming slightly annoyed by the second part while I read it, but then understanding its relevance to the whole once I reached the end of the novel. It would not have worked without the annoying, but still well-written, second section. My annoyance derived from the post-modern ploys that Auster adopted to achieve his end result, the relevance of which I understand, but I remained annoyed by them. But don't let this detract from the novel too much, the first and third sections are sublime. The third section takes the first two, builds on the structure they provide, and makes the entire novel into something enchanting and truly worthwhile. If you struggle a bit in the middle of the book, champion onward - you will be rewarded by a well-plotted literary detective novel that achieves several 'Ahah!' moments. Enjoy them.

Tracy Chevalier - Burning Bright

Tracy Chevalier - Burning Bright I expected more of Burning Bright, having been told that Chevalier wrote Girl With a Pearl Earring, which I've yet to read, but I have been told is good. I was not to be satisfied. In the book, Chevalier tries to depict London during the Romantic era, playing too with the ideas beloved by the Romantics, for example the beauty of the rural and the corruption of the urban. But her execution of these ideas is clumsy, and they almost lose relevance as a consequence, which the Romantics themselves would have lamented - Coleridge twists in his grave.

The plot progresses as follows. A family from the good rural areas up North, move down to London when opportunity calls. But they are led astray by the allures of the city - they end up poorer than they began, tales of woe hound them, one of the few thins to make their lives seem worthwhile is the assistance they are given by one Mr. William Blake, their neighbour in Lambeth. William Blake meets the two main characters of the book - a boy and a girl - for whom he tries to explain the nature of innocence and experience, an ongoing conversation in which Blake expounds on how everyone has some innocence and some experience in them, and that each person but finds themselves somewhere on the continuum. Rah rah! Enter caddish lad, all suave atop a military horse, who navigates a lady's innocence and makes her more experienced. Ho hum. The book had a lot of potential, there was so much that could be done with the character of William Blake and the people who surrounded him, but it was not to be.

Instead, somehow, Chevalier manages to take the good bits, peel many of them away, and trivialize what remains by turning it into something puerile and arbitrary. If you've read Songs of Innocence and Experience, then you'd know that Blake plays with the these notions deliberately, plays with ideas of religion, of youth, of age, of creation and destruction. Yes, these come through in Chevalier's story, but so obviously and clumsily that they are far less appreciable than in William Blake's poetry. I'd recommend that instead of reading this book, reading a biography of William Blake, read some of his poetry, and maybe read a bit about the history of London at the time.

Annie Dilard - The Maytrees

Rarely do I read a book that conjures images as vividly and imaginatively as those that Annie Dillard conjures in The Maytrees. A love story, the book charts the love of a couple living in Provincetown on the Eastern Coast of the United States: they give birth to a child, they rift, but where does love go? What happens to love? Does it vanish? remain? transform? Can you love more than one person at a time? What of children?

I consistently read passages of The Maytrees out to my wife, astounded by Dillard's ability to characterize moments and sensations perfectly, for example, "They shook hands and hers felt hot under sand like a sugar donut," (7) or "Lou saw the sun spread like a gull for its landing on the sea." (105) Both are beautiful comparisons and evoke the exact image, the exact sensation to make me, as a reader, feel and see what the author makes the characters feel and see in these moments.

The Maytrees is stately, it carried me on the ebbs and flows of its prose as it would a piece of driftwood, and I had to give in to the rhythms of it, let it speak to me slowly, occasionally overwhelmed, occasionally feeling as though I sat atop a wave and was glimpsing an horizon beyond the book. Ok, I'm over-writing now, but I simply wanted to say I thought the book beautiful, poignant, poetic. It will not suit everyone, not that much 'happens'. Much is shown for us to interpret and relay, but I believe that if you appreciate Dillard's writing style, I have but read The Writing Life, The Maytrees will reward you with equally good steadily unfurling beauty and truth about love.

Raymond E. Feist - The Serpentwar Saga and The Conclave of Shadows Trilogy

I've read these books a number of times. Having recently been moving country, staying in a friend's living room, finding an apartment,

moving, getting internet, signing contracts, getting work, etc, I needed something non-literary. I fly through these books when I read

them and they satisfy a strange urge for reading about heroes, battles, magic, etc. Feist does epic battles, multiple-world-spanning wars, and bad philosophy about gods and people well. The Serpentwar Saga probably contains one of my favourite books of his Rise of a Merchant Prince, in which the main character, Rupert Avery, tries to set up a trading empire. Feist details how Roo fails, has the chutzpah to try something phenomenal, triumphs, then loses a huge amount of money in the next book because of a war, after which he starts up again in an attempt to regain his wealth amidst the ashes of a burnt-out kingdom. Thrilling stuff. Just what I needed while dealing with admin and getting back into a working paper on risk aversion.

Thursday, October 22, 2009

Gender and Risk: Reviews of the Evidence

Posted by Simon Halliday | Thursday, October 22, 2009 | Category:

Behavioral Economics,

Economics,

Experiments,

Risk

|

4

comments

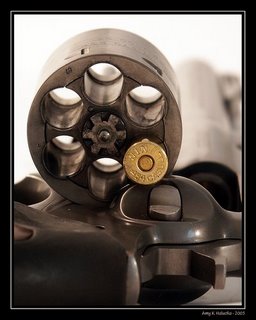

I begin my series on risk aversion, competition and gender with a review paper by Catherine Eckel and Philip J. Grossman in The Handbook of Experimental Economics Results. In their paper, Eckel and Grossman cover several papers that assess risk aversion. So what do we mean by risk aversion? We mean the tendency to avoid risk, to avoid a probability of winning or losing money relative to winning or losing some certain amount of money. For example, do you put your money under your bed, in property, in bonds, or in stocks? The level of risk increases as you move from the one to the other, but the potential rewards increase too - leading to the well-known relationship between risk and reward. Eckel and Grossman look at three methods used in economics to assess risk aversion - Abstract Gambles, Contextual Environment Experiments and Field Experiments. I deal with each in turn.

I begin my series on risk aversion, competition and gender with a review paper by Catherine Eckel and Philip J. Grossman in The Handbook of Experimental Economics Results. In their paper, Eckel and Grossman cover several papers that assess risk aversion. So what do we mean by risk aversion? We mean the tendency to avoid risk, to avoid a probability of winning or losing money relative to winning or losing some certain amount of money. For example, do you put your money under your bed, in property, in bonds, or in stocks? The level of risk increases as you move from the one to the other, but the potential rewards increase too - leading to the well-known relationship between risk and reward. Eckel and Grossman look at three methods used in economics to assess risk aversion - Abstract Gambles, Contextual Environment Experiments and Field Experiments. I deal with each in turn. Abstract gambles are decisions where a subject has to choose the gambles that they prefer, these decisions may be hypothetical (I'm not a fan), low stakes gambles (normally with some good, like chocolates or sweets), or be gambles with money that they are given by the experimenter. For example, the subject could be given $8, then asked whether they would like to participate in a gamble in which the rewards are -$8, -$3, $0, +$3, +$8, or they could just stick with $8. The subject could then leave with anywhere between $0 and $16. The experimenter could then vary the probabilities with which these events are likely to occur to evaluate risk aversion. Contextual Environment Experiments are characterised by abstract gambles, except that the decisions are framed differently, i.e. in the gain domain (getting positive amounts of money) something could be framed as an 'investment', in the loss domain something could be framed as 'insurance' (paying money to avoid something occurring in the future). Field survey and experiments, often coupled with laboratory gambles, evaluate subjects' behavior outside of the laboratory, either in some environment to which the subjects are accustomed, or in some experimental frame - seminal experiments evaluated subjects behavior in the laboratory compared to their behavior in an activity to which they are accustomed, in this case trading sports cards, or collecting coins, others simply report survey results and chart behavior.

Using abstract gambles with material incentives, the evidence indicates the following results, either men are less risk averse than women, meaning that men, particularly men from adolescence to about 40-years-old, choose more risky gambles than women do, or there are no statistically significant differences between men's and women's behavior. There is no evidence that men are more risk averse than women for gains. However, for losses, women are less risk averse than men, i.e. when faced with the option of losing money, women will take a risky gamble to lose a large amount of money, rather than lose money with certainty.

Using abstract gambles with material incentives, the evidence indicates the following results, either men are less risk averse than women, meaning that men, particularly men from adolescence to about 40-years-old, choose more risky gambles than women do, or there are no statistically significant differences between men's and women's behavior. There is no evidence that men are more risk averse than women for gains. However, for losses, women are less risk averse than men, i.e. when faced with the option of losing money, women will take a risky gamble to lose a large amount of money, rather than lose money with certainty.  In the contextual environment experiments, the frames change and behavior also changes as a consequence. As described above, when framing losses as insurance and gains as investments men's and women's behavior does not differ significantly in one pair of studies (Schubert et al, 1999, 2000), whereas in another (Moore and Eckel, 2003) women are significantly more risk averse than men and similar to the evidence for abstract gambles, women are more risk-seeking for insurance, i.e. risk-seeking for losses, and similarly in another study (Gysler, Kruse and Schubert, 2002) after controlling for competence, knowledge and over-confidence women are more risk averse than men with their risk aversion decreasing in their levels of expertise. A final study by Levy, Elron and Cohen (1999) with MBA students simulating a stock market shows women significantly more risk averse than men and making substantially less money as a consequence, this experiment is particularly interesting because the subjects supposedly gambled with their own money.

In the contextual environment experiments, the frames change and behavior also changes as a consequence. As described above, when framing losses as insurance and gains as investments men's and women's behavior does not differ significantly in one pair of studies (Schubert et al, 1999, 2000), whereas in another (Moore and Eckel, 2003) women are significantly more risk averse than men and similar to the evidence for abstract gambles, women are more risk-seeking for insurance, i.e. risk-seeking for losses, and similarly in another study (Gysler, Kruse and Schubert, 2002) after controlling for competence, knowledge and over-confidence women are more risk averse than men with their risk aversion decreasing in their levels of expertise. A final study by Levy, Elron and Cohen (1999) with MBA students simulating a stock market shows women significantly more risk averse than men and making substantially less money as a consequence, this experiment is particularly interesting because the subjects supposedly gambled with their own money.  Lastly, for field work, a substantial amount of data corroborates the result that women, particularly single women, are more risk averse than men. Several articles show that men hold more risky assets than women do - women tended to hold riskless, or relatively less risky, assets. Married women were also substantially less risk averse than single women throughout these data.

Lastly, for field work, a substantial amount of data corroborates the result that women, particularly single women, are more risk averse than men. Several articles show that men hold more risky assets than women do - women tended to hold riskless, or relatively less risky, assets. Married women were also substantially less risk averse than single women throughout these data. The results from these papers generally indicate that women are substantially more risk averse than men for gains, and women are more risk-loving than men for losses. Eckel and Grossman do not try to explain why women behave so, but rather try to chart the result's empirical regularity. We'll leave speculation about why women behave this way to later papers.

References

Eckel, Catherine and Philip J. Grossman, 2008, 'Men, Women and Risk Aversion', in The Handbook of Experimental Economics Results, Charles R. Plott and Vernon L. Smith (eds), Elsevier Science & North-Holland.

Gysler, M., J. B. Kruse, and R. Schubert. (2002). “Ambiguity and Gender Differences in Financial decision Making: An Experimental Examination of Competence and Confidence Effects.” Center for Economic Research, Swiss Federal Institute of Technology, Working Paper.

Levy, H., E. Elron and A. Cohen (1999). "Gender Differences in Risk Taking and Investment Behavior: An Experimental Analysis." Unpublished manuscript, The Hebrew University

Moore, E. and C. C. Eckel (2003). “Measuring Ambiguity Aversion.” Unpublished manuscript, Department of Economics, Virginia Tech.

Schubert, R., M.Gysler, M. Brown and H. W. Brachinger (1999). “Financial Decision-Making: Are Women Really More Risk Averse?” American Economic Review Papers and Proceedings 89:381-385.

Schubert, R., M.Gysler, M. Brown and H. W. Brachinger (2000). “Gender Specific Attitudes Towards Risk and Ambiguity: An Experimental Investigation.” Center for Economic Research, Swiss Federal Institute of Technology, Working Paper.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)