Thursday, April 23, 2009

Happiness Economics

Posted by Simon Halliday | Thursday, April 23, 2009 | Category:

Behavioural Economics,

Development,

Macroeconomics,

South Africa

|

My recent course on sustainable development included a module on the growing literature of happiness economics. It was included in a sustainable development course because of the trends that are observed in the 'happiness economics' literature regarding dissatisfaction with GDP as an index of human welfare and thus GDP growth as a measure of a society's advancement. I will attempt to deal with some of the questions that we covered in our class as prep for my exam next week. I am particularly interested to find data on this for South Africa as I believe we could find some interesting patterns in South Africa (more on which later, but mostly relating to South African economic inequality and its effects on happiness).

My recent course on sustainable development included a module on the growing literature of happiness economics. It was included in a sustainable development course because of the trends that are observed in the 'happiness economics' literature regarding dissatisfaction with GDP as an index of human welfare and thus GDP growth as a measure of a society's advancement. I will attempt to deal with some of the questions that we covered in our class as prep for my exam next week. I am particularly interested to find data on this for South Africa as I believe we could find some interesting patterns in South Africa (more on which later, but mostly relating to South African economic inequality and its effects on happiness). I want to clear a couple of areas of scepticism and introduce some of the 'problems' in Economics and why there are problems with economic methods and their relationship with happiness. In my second post I'll get onto the first paper about aspirations and happiness.

First a definition. Subjective wellbeing is normally measured using an index of either 1 to 5 or 1 to 10 points. The questions range from asking about 'happiness' to 'satisfaction'. Thus a 1 generally corresponds to completely dissatisfied or completely unhappy, and a 10 corresponds to completely satisfied or completely happy. It's called 'subjective' wellbeing because survey respondents are asked their opinion on their own levels of happiness, or wellbeing, i.e. currently we have no 'objective' method to measure happiness.

Second, to clear some questions about cultural differences and comparisons across countries I believe it is arbitrary to state (as we see in the media so regularly) that Country X is happier than Country Y. There may be all kinds of cultural factors, say reservedness, which affect how people report happiness, or more accurately 'subjective wellbeing'. However, it is completely acceptable to compare trends across countries, for example to state that subjective wellbeing in America and the United Kingdom has decreased dramatically over the past 30 years, whereas in Europe subjective wellbeing has either increased or remained constant over the same period. Why do we accept the trend comparisons and not the absolute comparisons? To compare absolute levels between countries lacks nuance and does not take account of factors endemic to that country, say British reservedness (as I mentioned above). Comparing within country trends however assumes that something like culture remains constant within a country, so, holding British reservedness constant over the past 30 years, why has their subjective wellbeing decreased, while in the same period subjective wellbeing in Denmark has increased? That

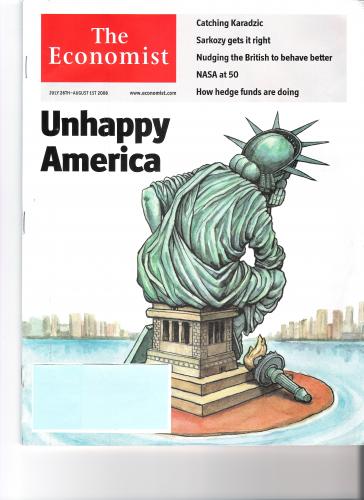

Second, to clear some questions about cultural differences and comparisons across countries I believe it is arbitrary to state (as we see in the media so regularly) that Country X is happier than Country Y. There may be all kinds of cultural factors, say reservedness, which affect how people report happiness, or more accurately 'subjective wellbeing'. However, it is completely acceptable to compare trends across countries, for example to state that subjective wellbeing in America and the United Kingdom has decreased dramatically over the past 30 years, whereas in Europe subjective wellbeing has either increased or remained constant over the same period. Why do we accept the trend comparisons and not the absolute comparisons? To compare absolute levels between countries lacks nuance and does not take account of factors endemic to that country, say British reservedness (as I mentioned above). Comparing within country trends however assumes that something like culture remains constant within a country, so, holding British reservedness constant over the past 30 years, why has their subjective wellbeing decreased, while in the same period subjective wellbeing in Denmark has increased? That  comparison is legitimate and allows us to explore the factors that affect each country. Note too that average economic growth in the US and UK has exceeded that of Europe on average, which leaves us with the happiness paradox - more growth (i.e. objectively more stuff), but people are less happy.

comparison is legitimate and allows us to explore the factors that affect each country. Note too that average economic growth in the US and UK has exceeded that of Europe on average, which leaves us with the happiness paradox - more growth (i.e. objectively more stuff), but people are less happy. Third, I want to annunciate the problem clearly (and somewhat technically). In basic economics individuals get something called 'utility' derived from acts of consumption where consumption can include eating food, seeing a movie, taking an airplane flight, or purchasing insurance. From this we can derive what we call a utility function - a mathematical representation of peoples' utility that contains information on what they consume.

A utility function looks like this: U = f(x) where x can be a 'vector' (read as a list) of goods that a person consumes, the basic idea being here that if you choose, say, to eat a banana then you have derived utility from doing so, similarly for buying a chair, watching a movie, and so on.

Now, the problem arrives. If we can say that utility should correlate with subjective wellbeing or happiness (if it isn't then many people are uncertain what it really measures), then having more money on average should make people happier. They can consume more because money is instrumental to consuming more. By this reasoning people in the US and the UK should have been getting happier over time, and we could probably even say that they should have been getting happier more quickly than people in countries that were not growing as quickly. But, the opposite is true! Brits and Americans have become unhappier over time. The graph adjacent depicts US happiness and US GDP per capita over a period of 50 years (one of my prof's slides). The trend is similar (though not quite as dire) for the UK. It is quite dissimilar for the most of the EU - Italy, France, Germany, Denmark, Sweden and the Netherlands.

I will address some of the reasons why we observe this happiness paradox in my next few posts, some of the motivations will deal with flaws in the utility function (it only measures absolute gains, not relative gains and losses, or gains and losses relative to some group), to the problem of 'negative endogenous growth' (not as difficult to consider as it sounds), the degeneration of social capital, and I will offer some stylised facts that may offer some insight. I will also try to read some of the literature on developing countries, specifically I have found one paper on subjective wellbeing in South Africa from data in 1993 and I will comment on that when I have the time.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

Currently have 0 comments:

Post a Comment